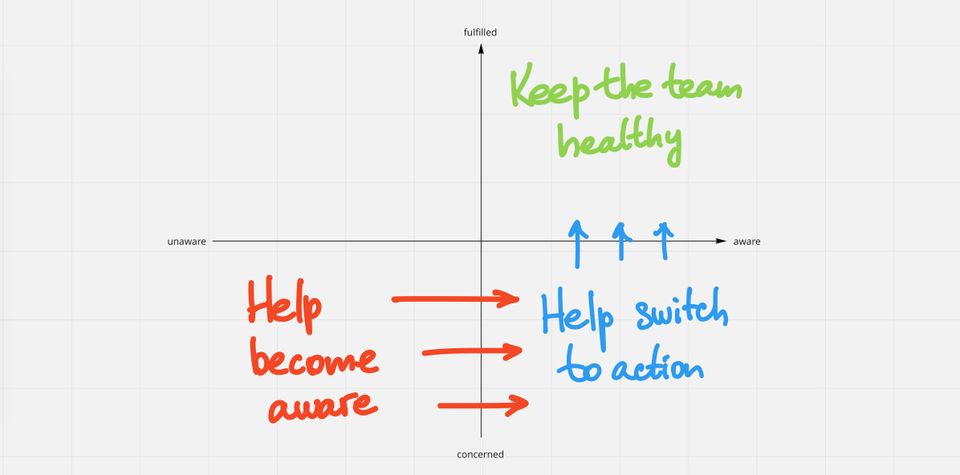

Awareness vs. concern

As an engineering manager, how do you tell whether the team is healthy? You sure follow some metrics, but teams consist of people, and you can’t just measure people. If you optimize for team health and expect operational efficiency as a side-effect of that (and not the other way around), you really want to focus on people and where their minds are at. One proxy to team health is how each individual person on the team perceives their surroundings. I found a simple model of “awareness vs. concern” very effective.

Awareness is really about how clearly each person on the team sees the situation. Are they real about what’s happening, or are they more inclined towards certain emotion based on short-living emotion and rumors? Do they understand all the challenges that the team is going through internally, or are they just happy to be here? By virtue of being a people manager on the team, you have access to minds of all the people there, and because you are first and foremost responsible for the team’s success, it’s your job to figure our what’s going on in those minds, — at least when it comes to working together.

Concern is sum of each person’s optimism minus sum of their dissatisfaction. People might be going through moments of euphoria, moments of micro-despair, but it’s the total value that matters. If someone is more pessimistic than not, even if they appear happy on Fridays, they probably hold some concerns, and you really want to understand what exactly. But just before doing that, you need to make sure you address people in order of priority: that is, most concerned first.

So now we have two dimensions to evaluate each individual on. Let’s walk through them.

Aware and not concerned

The best place to be! If someone is aware of all the challenges and problems on the team, but remain mostly positive and optimistic, they are among the most equipped to actually fix those issues, — and! they likely have enough energy to do that.

With people who are aware and not concerned, you can work productively towards keeping the team healthy.

Of course, you also need to dedicate time to them personally. There are rituals for that, such as one-on-one conversations, discussing professional development and future career progression, and making sure they are presented with a range of opportunities they need and deserve.

Aware, but concerned

This is the spot where people get most real. For you as a manager, it’s a perfect challenge to open these people up and listen carefully to what they say.

It’s important to gradually stop talking about how things are and start changing the narrative towards taking action. While talking through a problem help refine the understanding of that problem, this, repeated a couple times, can turn the discussion into a therapy session and participants into a pair of emotional sponge.

One mistake I’ve seen folks making and certainly made myself is recommending to take action too early. It’s tempting, hearing “what we do isn’t working”, to say “what did you do to fix this?”, but this can be perceived as too cold-blooded or pushy by some people. Carefully leading such discussion to an outcome that would benefit the team and that person is hard, and that’s a topic for another story.

The thing is, your goal is not to forcefully pull someone who is aware and concerned into the area of being less concerned. Instead, your goal is to get them take more action. Only through action they take, will they become more satisfied with how things are and thus less concerned.

Unaware and not concerned

The third quadrant is not really being concerned, but not being aware either. You might have guessed that there are situations like that all the time: when people had just joined the company! Unless they have decades of experience, super high expectations, and are suffering from lack of ability to adapt, they’ll probably be unconcerned for quite some time, regardless of how poorly structured or dysfunctional the environment is, because they’re learning. But this should come to an end at some point.

Most people graduate from this category after staying for a few months on your team. That’s when they start seeing problems, — or not! It’s also possible that some team members become more aware but remain mostly unconcerned, perhaps pointing at minor issues here and there that are trivial to fix.

If someone stays for too long in this state, either they’re not growing professionally, to which being always satisfied with how things are is a proxy, or you’re doing something fundamentally right for the team and you should start teaching other managers to do the same, because this is a really fantastic achievement. If it’s the latter, congratulations! If it’s the former, the one who should be concerned is now you.

Unaware, but concerned

There can be a situation when someone on the team is not really aware of what’s going on, in terms of team operations and health, and yet they’re concerned. They point out problems, but there problems are either in process of being fixed, or are agreed upon by the team as being of low priority, or are non-existent. They might occasionally point out a true urgent problem, but if you sense that’s more opportunistic and less of an informed claim, then you’re listening to someone who is concerned, but not really aware of the situation. They’re lacking context, and now you need to figure out why.

If a person who is not yet aware of what’s going on on the team in terms of how people work together, yet appears concerned, you need to carefully evaluate what’s going on. Are they just always unhappy with stuff? Are they traumatized by experience in a previous team and can’t get over it? It’s very important you don’t take shortcuts here, so that you don’t make decisions that are hard to reverse too early.

You first goal here is to get the person aware. Consequently, your first goal should not be to get them less concerned. In practice, this means saying less of “things aren’t as bad” and asking more of “what evidence is there that proves things are bad?”

Putting it all together

Alright, let’s flex some visual thinking skills! Take a piece of paper or open your favorite canvas app and draw two axes. One axis goes from “unaware” to “aware”, the other from “concerned” to “fulfilled”.

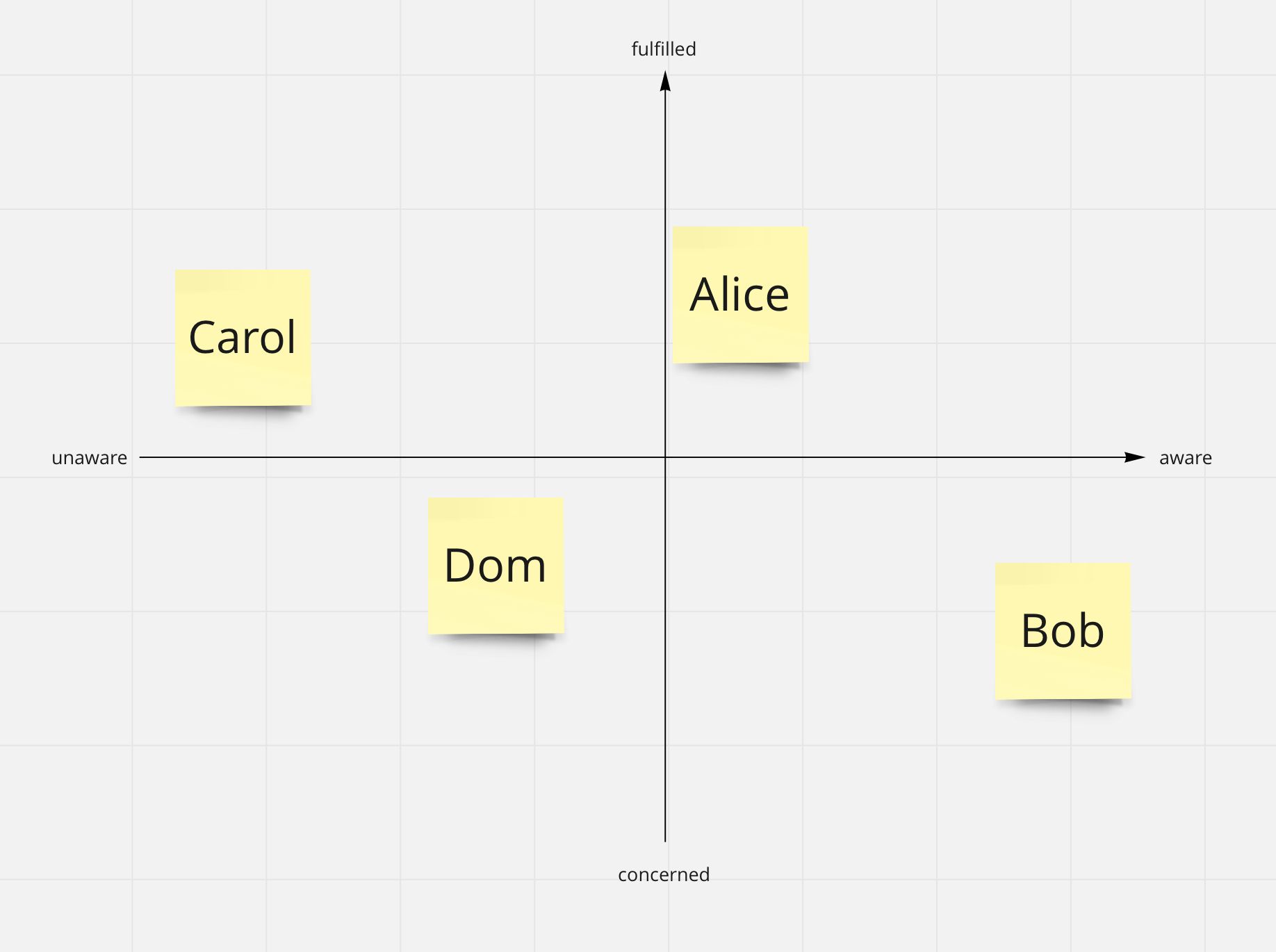

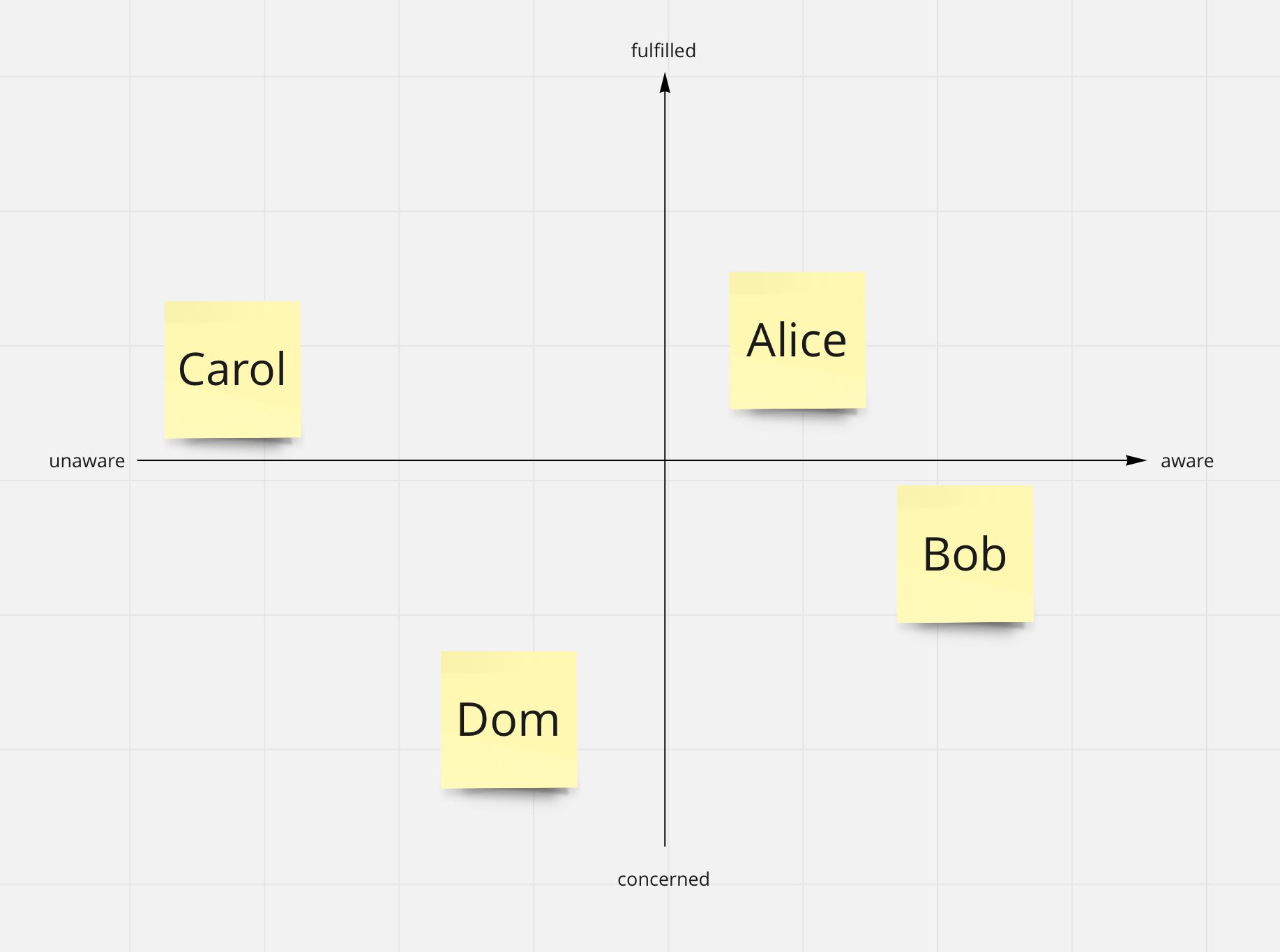

If you do one-on-one conversations with the people on your team, chances are, you already have enough material to reduce into coordinates at which to position that person.

Once you have all the people on the chart, you can calibrate. Is Bob as much more aware, compared to Alice, or not quite yet? Are you being too soft on Dom and inadvertently avoiding hard truth? So, calibrate!

Done? Spectactular! Now you have a good understanding of the order of priority and a good sense for how to distribute the time you spend with the people and what to focus on in the conversations.

But more importantly, now you can see at a glance whether the team is healthy. It doesn’t give you the answer to why — yet. Now you can fine-tune your 1x1s with the team members and make sure people are moving in the right direction on the awareness-concern plane.

Keep in mind that this is just a mental model! It’s not intended to give you information at level of accuracy or precision that would turn it into data you could analyze. It’s purely a thinking aid and is supposed to offload some of your brain capacity onto paper or some visual canvas app. It’s one of those soft skills things that no software, for better or worse, can get done for you. Still, I personally find it easier to explain things to myself and other people when they are laid out visually: a picture can tell a story much better than a stream of words.